|

Shalom y'all!!

Welcome to this week’s episode of Better Know a Jewish Holiday: Shabbat!! The fightin’ day of rest!!

Now, unlike just about every other Jewish holiday, shabbat doesn’t just come around once a year, we get shabbat every week!

First, the basics. Shabbat starts every week at sundown on Friday and concludes Saturday night when there are three stars in the sky.

As noted above, shabbat is considered a “day of rest” and is meant to feel distinctly different from the rest of the week. Read on to find out how we got this shabbat thing in the first place, what the rules are for shabbat, and how we celebrate:

Now, why do we have a holiday every week? Great question! It all goes back to the beginning of time. According to Jewish tradition, God created the world in six days.

And the end of the sixth day, God took a peek at everything God had created and saw that it was all very good.

And then God was all like: “Wow, world creation is really hard work, boy do I need a shluf!” (yiddish for ‘nap’) So the bible tells us that on the seventh day, God rested.

Fast forward a number of years and everyone had forgotten how important it was to take a day off. People were running around the world overworking themselves.

Not only that, but slavery was all the rage and the Israelites were slaves in Egypt. So they didn’t really have any say over they own time or if they ever got a break.

As you might remember from Better Know Passover God eventually came and redeemed the Jews from slavery in Egypt. There were plagues, it got messy, moving on.

Once the Jews are out in the desert, God starts to lay down the laws. There are a lot of them. The Israelites are basically learning to build a society from scratch so they’re learning everything from how property transfer should work to moral codes to what sacrifices God expects from them to the fact that a woman is not allowed to intercede in a fight between two men by grabbing the testicles of one of the combatants:

Pardon my tangent, there’s just so much fun stuff in Torah. Anyway, quite a number of the commandments given to the Jews deal with this “shabbat” thing. For the first time, there’s a day that’s mandated as a day of rest, and we Jews take our rest VERY seriously.

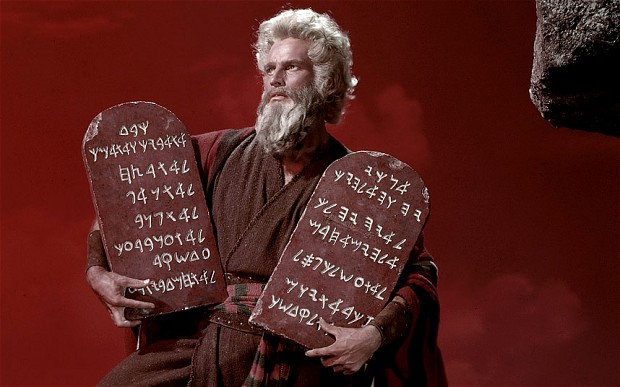

Shabbat is one of the 10 Commandments, which means it’s obvs v important, but what many people don’t know is the 10 Commandments actually appear twice in the Bible.

The first time, the commandment is to “Remember the Shabbat” and the second time the commandment is to “Keep/Observe the Shabbat.”

Good question. The rabbis interpret the command “Remember” to mean we have to perform all of the positive commandments for shabbat (you must do this, you must do that), while “Keep/Observe” is the commandment to NOT do all of the negative commandments.

It’s important to mention here that different Jews remember and observe shabbat in different ways. What I’ll be explaining here are some of the traditional practices for shabbat but three Jews will have five different ideas about what shabbat should look like exactly.

So, the positive commandments, what are the things we’re supposed to do on shabbat? Well, they include: lighting candles to mark the beginning of the holiday, saying a blessing over wine, having three delicious meals, attending synagogue on Friday night and/or Saturday morning, hearing a reading from the Torah (first five books of the Bible), RESTING, and enjoying ourselves.

It should also be noted that the commandment to rest also extends to everyone in the household including animals and servants. The idea is not just that the wealthy would have a day off but that every single person would have a day of rest.

But what about the negative commandments, what are Jews not supposed to do on Shabbat? Well, in the Torah we read that the Jews were not allowed to continue their work building the tabernacle (like a traveling tent-temple thing) on Shabbat. There are 39 types of work outlined for the building of that structure, so all our current laws are derivative from those original 39.

Basically it means that there’s a lot of stuff that’s not allowed. Traditional Jews do not drive cars on shabbat or turn on lights (these prohibitions come from the original prohibition against lighting a fire). Jews do not traditionally cook on shabbat, don’t spend money, and they don’t carry things from place to place.

The full list of things we’re not allowed to do on shabbat fills up many books.

These “don’ts” were instituted to prevent people from doing work and to ensure that they rested. Think of it this way: All the things we’re not allowed to do are intended to give us the space to do all the things we never get enough time to do: talk to people face to face, spend time with loved ones, read a good book, a newspaper, maybe even The New Yorker.

Shabbat ends with an amazing ceremony called “havdallah” which literally means separation. We light a candle with multiple wicks, smell sweet spices, drink more wine, and prepare ourselves to move into the coming week.

If you have questions about specific shabbat do’s and don’ts please feel free to ask in the comments below and I’ll get back to you!

In the meantime, happy resting!

Upon further reflection, while this post does cover the basics of shabbat and its observance, it fails to capture the spiritual essence of what this day really means. Abraham Joshua Heschel called shabbat "a palace in time" and when you take this day out of your week to rest, to reflect, to be with friends and family, it can truly change the character not only of Friday night and Saturday but the rest of the week as well.

In the future I will try to craft another post that does shabbat justice in all of its world-changing abilities.

0 Comments

Last night I had an amazing experience at The Kotel (Western Wall). I haven't been able to say that for some time. As I made my way into the Ancient City of Jerusalem, I joined in a throng of people headed to the wall that most closely resembled the crowds heading into a football stadium on Game Day on college campuses across America. The wall has been a flashpoint ever since Israel took control of the old city 50 years ago. In recent years, I have become much less comfortable praying at the wall both because praying to a wall seems somewhat un-Jewish and due to the horrendous treatment of women by the Western Wall Heritage Foundation (which oversees the wall), which is a חילול ה׳ a desecration of God's name. But last night, I gathered with tens of thousands of Jews at the wall for Selichot, the penitentiary prayers said in the days leading up to Yom Kippur, the day of judgement. If you were able to get close enough to the wall there were still the divided men's and women's sections, but where I was standing there was a true ערב רב, a mixed multitude of people. Ultra-orthodox men stood next to secular women and vice versa. Jews whose families came to Israel from Iraq and Morocco stood shoulder to shoulder with those who arrived from Poland and recent immigrants from America. We stood together in prayer, collectively chanted חטאנו לפניך רחם עלינו (we have sinned before you, have mercy on us). In the Avodah service read during the late morning (or early afternoon) on Yom Kippur we recall how in the days of the Temple the high priest would go into the holy of holies and pronounce the name of God, and when he would do so the Israelites in the courtyard would respond with a formulation found in the Torah as God's own description of Godsself:

ה׳ ה׳ אֵ֥ל רַח֖וּם וְחַנּ֑וּן אֶ֥רֶךְ אַפַּ֖יִם וְרַב־חֶ֥סֶד וֶאֱמֶֽת נֹצֵ֥ר חֶ֙סֶד֙ לָאֲלָפִ֔ים נֹשֵׂ֥א עָוון וָפֶ֖שַׁע וְחַטָּאָ֑ה וְנַקֵּה֙ “The LORD! the LORD! a God compassionate and gracious, slow to anger, abounding in kindness and faithfulness, extending kindness to the thousandth generation, forgiving iniquity, transgression, and sin״ Two thousand years later, I stood on the same ground, just outside the courtyard where they would gather. I recited that same formula, word for word, with a massive Jewish community gathered for the same purpose, to seek atonement. We did not come together to worship a Wall, but in this moment the Wall served the same purpose the Temple did 2,000 years ago: it became our common focal point, the gravitational center that brought us all together. To be clear, the Jewish/Israelite community of the Second Temple period was far from perfect. The infighting amongst factions and the disrespect showed to fellow Jews ended up being the downfall of the Temple that once stood upon this mount. As we begin the Yom Kippur fast let us open our ears to the timeless call of Isaiah, who lived in Jerusalem and saw with his own eyes the destruction that comes when Jews do not care for those who need help most: "Is this the fast I desire?" Isaiah calls out to us during the haftorah reading on Yom Kippur morning, "A day for people to starve their bodies?" "No," he responds, "It is to share your bread with the hungry, And to take the poor into your home; When you see the naked, to clothe him, And not to ignore your own kin." I hope against hope and I pray with all my heart that the year 5778 will be a year that brings us together as a Jewish people and as a human race. That it will be a year when we differentiate ourselves from our ancestors by choosing love and compassion over fear and strife and סינת חינם (senseless hatred). That it be a year that we dedicate ourselves to bringing more justice, more light, and more truth into the world. In the words of R' Natan Sternhartz: May all who live on earth come to realize realize We have not come into being to hate or to destroy. We have come into being To praise, to labor, and to love. Wishing a meaningful Yom Kippur to all those who will be observing and a meaningful year to us all. גמר חתימה טובה בספר החיים, בספר רפואה, בספר שמחה, ובספר שלום May we all be written and sealed in the book of life, of good health, of joy, and of peace. שנה טובה (Shana Tovah) A happy new year to everyone! It's been quite the year transitioning to rabbinical school, and I'm going to do my best to keep the site a bit more active this coming year. To start the year, I wanted to share something a bit more serious than the normal fare here on The More Jew Know. The following is a personal reflection I shared last year from the Bimah (the "stage" at the front of the synagogue) on the second day of Rosh Ha'Shannah at Beth Israel Congregation in Ann Arbor, Michigan. It's a lot more words, and a lot fewer gifs than you're used to if you come here often, but I hope you find it meaningful. I started trying to write about the sounding of the shofar, but I’m going to do something a little bit different. I’m going to speak to you about a still small voice. A קול דממה דקה (Kol Dmama Daka). This is a voice that is only heard immediately after the shofar stops its call... and it reaches out to us through the silence that follows. We learn about this voice in the Unetane Tokef, the prayer we say during the musaf amidah when the chazan chants that a שׁוֹפָר גָּדוֹל יִתָּקַע!! A great shofar will sound!! וְקוֹל דְּמָמָה דַקָּה יִשָּׁמַע. And a still thin voice will be heard. And then the imagery that follows is both fantastic and terrifying: מַלְאָכִים יֵחָפֵזוּן Angels will hasten, וְחִיל וּרְעָדָה יֹאחֵזוּן a trembling and terror will seize them. What is it about this still small voice that makes it more impactful than the great blasts of the shofar? Why are the angels trembling with terror from this kol dmama daka? In the bible, the only place we hear of a kol dmama daka, the still, small voice, is in the book of מלכים, Kings, when Elijah is alone on the top of Har Carmel in northern Israel. Like our post-shofar silence, the kol dmama comes to Elijah only after his senses have been assaulted. First with a strong wind, then an earthquake, then a fire. Elijah looks and listens for God in each of these, but “the LORD was not in them.” When the voice, the small still voice finally comes, it asks him “מַה-לְּךָ פֹה אֵלִיָּהוּ” What are you doing here Elijah? It is that question, that haunting question that is there in the air hanging after we hear the sound of the shofar. “What are you doing here?” “What am I doing here?” Some years our answer to that question seems very clear, other years it’s half formed, and some years we are at a complete loss. But for that moment, that sweet and terrifying instant, when the קול דממה דקה talks to us, questions us, demand that we face this most basic question, that is the essence of ראש השנה (Rosh Hashannah) for me. But then why bother with the shofar at all? Why is it that we cannot simply all sit silently and wait to hear this still thin voice? Why not simply meditate in silence and wait for its appearance? Why do we only hear the קול דממה דקה, the kol dmama daka, after the שׁוֹפָר גָּדוֹל יִתָּקַע (shofar gadol itaka) the great blasts of the Shofar? Is it because you truly can’t have one without the other? For one thing, the Torah refers to Rosh HaShannah as Yom Truah, the day of blasts, so it would be difficult to blow it off completely. But that’s not the only reason for the sounding of the shofar… I don’t know about any of you, but when the shofar blows it consumes my mind and body. I am able to focus solely on the sound of the ram’s horn, feeling its vibrations in my bones, and when it ends I feel as though I am partially empty, like I had just been filled with this magic, transcendent substance that has been all of a sudden flushed away, leaving behind a shell, a cavity. It is into that space that the kol dmama daka comes in. Without allowing ourselves to become lost in the sound of the shofar letting it fill us up with its sound, we cannot make space for the still and small voice. So when the shofar sounds now, try to lose yourself in its call and be ready for the silence immediately after, when the קול דממה דקה (kol dmama daka) comes to ask us, “why are we here?” Wishing a sweet new year to all those celebrating, and may we all be inscribed in the book of life!

שנה טובה ומתוקה!!! Shana Tovah U'Metukah!! Shalom y’all and welcome to this week’s edition of Better Know a Jewish Holiday. Today we’re talking Sukkot: The fightin’ Feast of Booths!! Sukkot (soo-KOTE) is a weeklong holiday that begins five days after Yom Kippur ends—so Sunday night! During this holiday Jews traditionally build little huts outside their homes and live in them for the duration of the week. The huts—which are called sukkot, singular is Sukkah (soo-KAH or SOO-kah)—are supposed to give the feeling of being in temporary shelters rather than our more sturdy homes. Living in the huts is meant to remind us of fragile structures our ancestors lived in when they were traveling in the desert for 40 years after leaving slavery in Egypt before arriving in Israel. There are a few basic rules for a sukkah: They must be at least three-sided: They have to be temporary (i.e. you can’t put a room onto your house and call it the sukkah room) And the roofs are made of branches called s’chach which are supposed to cover more than half the roof but leave enough space so that you can see the stars. I’m not giving you a pronouncer on s’chach because if you can't say it already, you'll probably just end up looking like this: As long as weather permits, we are supposed to do pretty much everything in the sukkah. Specifically, we’re supposed to eat all of our meals in the hut and try to sleep in it, as long as it’s not too uncomfortable. Some fun/alliterative/rhyming/clever Sukkah activities can include: Sushi in the sukkah, Pizza in the hut, You can also doCider in the Sukkah, or (as my friend Alex Zaremba pioneered) Sukkot with a Goat. And you know what that means… MORE GOAT GIFS: Sukkot is also one of three holidays (the others being Passover and Shavuot, which you may remember from previous episodes of Better Know a Jewish Holiday) when all of the Jews living in ancient Israel would make pilgrimages up to the Temple in Jerusalem. They would bring the first fruits of their harvest to give as a tithe/sacrifice for the holiday. The last interesting element of Sukkot that we will delve into with this email is the shaking of the lulav (LOO-lahv) and etrog (ET-roge), which are shown off by this cheery looking fellow. As you can see, this is a collection of plants that we hold together and then shake in all directions in the sukkah. The lulav is made up of a palm frond, a couple myrtle branches, and a couple willow branches. The Etrog is a tart lemon-like citron with a little pointy tip. People in Israel pay hundreds of dollars for perfect etrogs and they have them checked for blemishes by rabbis: Unlike a certain other Jewish custom, in this case it’s very important that the tip stay ON the etrog, or else it’s not kosher. There are many theories/reasons the rabbis give for the lulav and etrog, but the one I like the most is that we hold these four things together to represent the different kinds of people in our community. A palm front has taste but no smell, myrtle has smell but no taste, willow has neither and etrog has both. We are only strong as a community when appreciate people with all of their different talents, skills, abilities, shortcomings and differences. So on sukkot we go in the sukkah and we take the lulav and etrog and shake them all around. We shake it up, down, left right and all around to remind ourselves that G-d is everywhere. Sukkot is also known as Z’man Simchateinu, and the Rabbis say we’re supposed to be happy for the whole week! Final bonus Sukkot fun fact!! When christmas season is over in America, the christmas light producers unload a lot of their extra materials on the super religious parts of Jerusalem for people decorating their Sukkot. This includes large statues of Santa Claus, because when you give a bunch of Jews a large man with white facial hair, they think something else: So have a great and happy week everyone, whether you’re celebrating sukkot or not!

You can great your Jewish friends next week by saying: Good Yontif! (YON-tiff or YAHN-tiff, probably depending on which shtetl your great grandparents came from, kinda rhymes with Pontiff) Shalom y’all and welcome to Better Know a Jewish Holiday: Yom Kippur! The Fightin’ Day of Atonement! As the second of the “High Holidays,” Yom Kippur is considered a pretty big deal in the Jewish community. For many Jews, it’s one of the few holidays they celebrate and synagogue/temple attendance skyrockets The holiday begins Tuesday evening this year with Kol Nidre (Kohl Need-ray). Yom Kippur kicks off with an evening service, whose name is taken from the major prayer we say and literally means “all my vows.” Kol Nidre is a renunciation of all vows and oaths taken in the prior year. It was developed at a time when people took vows much more seriously and yet would often make vows/oaths they simply could not keep. It gave everyone a blank slate heading into the new year. The prayer took on new meaning and importance during the Spanish Inquisition and other times when Jews were persecuted and forcibly converted. Many Jews saw Kol Nidre as an opportunity to call take-backsies on those conversions. Now, on to the day itself: Most people associate Yom Kippur with atonement, or seeking pardon for our sins. For the 10 days leading up to Yom Kippur Jews will be apologizing to people for everything they’ve done wrong over the past year. In Jewish tradition, before God can forgive you for any sins, the person who you wronged has to accept your apology. I’d like to go ahead and get this out of the way. I know I probably slighted many of you at some point this year soooo: In ancient times, atoning for our sins was done communally and the entire Israelite people would gather in Jerusalem to ask God for forgiveness. The high priest would take two goats and would cast lots (draw straws) to determine which would be the community’s literal “scapegoat.” On Yom Kippur, the High Priest would place his hands on one of the goats and figuratively (or literally, depending on how seriously you take this) would transfer the sins of the entire Jewish people onto the goat. The goat would the be led off into the wilderness in order to rid the community of the sins. We don’t use goats any more, but the idea of passing our sins onto an animal is alive and well. The tradition of Kaparot, done during the 10 days between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, includes waving a live chicken over your head in order to symbolically transfer sins into the bird. On Yom Kippur itself we spend most of the day in synagogue praying and beating our chests. This is our last chance to be sealed in the Book of Life so we really try to make it count. Tradition holds that G-d writes us all in the Book of Life or Book of Death on Rosh Ha’Shana (which you all learned about 10 days ago) and then seals the books on Yom Kippur. As many people know, Yom Kippur is a fast day. I found a great piece last year in which a University of Michigan student uses Amy Schumer gifs to explain what fasting is like, so I’ll just send you to her excellent work. Despite all the fasting and chest beating, Yom Kippur was said by many Rabbis to be one of the happiest days of the year! Some, such as The Vilna Gaon and Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik go so far as to tie the holiday to the festival of Purim—when we dress up in costumes and are told to party hard—whose name shares the same Hebrew root as Yom Kippur. So why is it a happy day? There are no shortage of reasons given, but I like to think that it’s because this day is such an incredible opportunity. We no longer send goats off into the desert to atone for our sins. We get a chance to speak one-on-one with God and ask for forgiveness and to be given another year to do as much good in the world as we can. We also read the whole book of Jonah! In the end, the shofar sounds one more time (go back and read the Rosh Hashana missive if you forget what that is) and then we all go and eat yummy foods at big break fast parties! So, wish all the Jews in your life a “G’mar chatima tova!” (Gmahr Khah-tee-mah toe-vah and that’s a hard g on the front), which literally means a good final sealing but essentially means “may you be inscribed [in the Book of Life].” To all who are fasting have an easy and meaningful fast. Ben No, I don’t have an obsession with goat gifs. You have an obsession with goat gifs

Shalom Y'all!

Welcome to this week’s edition of Better Know a Jewish Holiday: Rosh Ha’Shanah!! The fightin’ New Year!!

For my own personal Rosh Ha’shannah resolution I’m going to re-do The More Jew Know so it’s more user-friendly and easy to navigate. I will also commit to getting the holiday posts up at least a week ahead of time instead of a day.

So, on to the main event: As some of you may know, Rosh Ha’Shannah (Rowsh hah-shah-NAH or hah-SHAH-nah) is celebrated as the new year, despite being the first day of the seventh month of the Jewish Calendar.

Technically, the first month of the Jewish calendar is in the spring, which makes sense because it’s a time of new beginnings.

However, this is the time we were told to celebrate so we go with it. The words “Rosh Ha’Shanah” literally translate to “Head of the Year” and it is actually never referred to by that name in the Bible. Instead, the holiday is called “Yom T’ruah”, which loosely translates to “The Day of of the Sounding of the Shofar.”

The shofar (show-FAR) is a rams horn blown throughout services during the holidays…

Okay, now that we’ve gotten that out of our systems… the shofar is blown in different cadences throughout the day.To demonstrate, I present to you, Jim the Shofar man (you should really watch this, he’s wearing an awesome robe):

While there is no explanation in the bible for why the shofar is blown, it’s sound has come to resonate with deep meaning to many Jews.

To some, the sound is an alarm clock, waking them up to the reality of the world around them and calling them to start the new year with a fresh outlook:

To others, it’s a clarion call urging them to reexamine their actions and commit to living a better life and making the world a better place.

The shofar is also a sound that has been heard across generations of Jews. Tradition holds that when the 600,000 Jews who left Egypt stood before Mt. Sinai to get the Torah from God, they heard the sound of the Shofar all around them. The shofar in my room belonged to my great-great-grandfather, and possibly to his father before him.

Personally, the shofar means all of these things in different years and can even mean them all at different times throughout the day. It’s a piercing sound that gets under my skin and both comforts and challenges me.

Rosh Ha’Shanah is a holiday of deep self reflection and we spend much of the day in synagogue thinking about who we have been over the past year and where we are going.

There are too many good “who am I” gifs to pick just one:

Rosh Ha’shana is the first of two “high holidays.” The second, Yom Kippur, arrives 10 days later.

Tradition holds that on Rosh Hashanah God writes us in the book of death or the book of life, then we have 10 days to cram in as much repentance as possible before he seals the books on Yom Kippur.

Rosh Ha’Shanah begins Sunday night and lasts through Tuesday evening. Unlike many other cultural new years, we do not get fireworks or cool costumes.

During our festive meals, we traditionally bring in a sweet new year by eating apples and honey, as well as honey cake, tzimmus (candied fruit with honey), and often just honey.

Bonus Rosh Ha’Shana fun fact: On the afternoon of the first day, we go to a body of water (usually running water like a river or stream) and empty out our pockets or toss bread crumbs in during a ceremony called Tashlich (TAHSH-likh)

The crumbs are symbolic of the sins and other baggage we’re leaving behind as we enter the New Year.

So, without further ado, I wish all of you a sweet, healthy, and happy new year full of meaning and joy.

Shana Tova u’Metukah (Shah-NAH Toe-VAH oo-meh-too-KAH)! Shalom y’all from one of the most beautiful places in the world, Camp Tel Yehudah! Welcome to this episode of Better Know a Jewish Holiday! Saturday night marks the beginning of the Shavuot; The fighting feast of weeks! Shavuot (shah-voo-OHT) is a multifaceted holiday with a wide variety of meanings and traditions. No, it’s fine. I’ll walk you through it. Jews spend the 49 days after Passover counting down to Shavuot, a process called the Omer. For more information on that process, you can check out our helpful Lag Ba’Omer post. As the Omer comes to an end, we reach two major events in Jewish history. The first, well, is kind of a big deal. After crossing the Red Sea, the Jews wander around for just a little while until they find themselves at Mt. Sinai. There they get ready to receive the Torah, the central text and teaching of Jewish tradition. According to the Torah, G-d decides (s)he’s going to speak directly to the Jewish people and give them the Ten Commandments. As one might expect, hearing the voice of G-d was just a liiiiiiitle too much for the Israelites. So Moses went up instead to get the Ten Commandments and the rest of the Torah. We all know how it went from there. The giving/receiving of the Torah was a monumental moment for the Jewish people and the world. It forms the backbone of the three monotheistic religions that together make up more than half of the world’s population. This year, there’s a beautiful coincidence, pointed out by my soon-to-be rabbinical school classmate Ben Perlstein: “What is particularly amazing about Shavuot this year is that it falls during another season of sacred counting and revelation: the Muslim month of Ramadan. Because the Muslim calendar—unlike the Jewish calendar—follows a lunar cycle with no leap years, Ramadan travels through the seasons from year to year, and so this overlap between Jewish and Muslim revelation holidays does not happen very often.” “What is even more amazing about how Shavuot and Ramadan are slated to coincide is that over these next few observances Shavuot will consistently fall within a day of the sixth night of Ramadan… and a Muslim hadith tells us that the Torah was revealed to the prophet Muhammed on the sixth night of Ramadan (Musnad Ahmad 16536).” I just find that really cool and awesome and wanted to share. There’s a lot more about the whole “getting the Torah” thing, but I’ve been working for the past week and a half to prepare this place for 140 16-year-olds to show up so you’re getting a bit of an abridged version. On to other things about Shavuot, Much like today’s American Jewish community, the Jews who lived in ancient Israel were an agricultural people. Okay, now that we got that out of our system. Shavuot was the holiday marking the bringing of the first fruits to the Temple in Jerusalem. Another name for the holiday is Chag Ha-Bikkurim, which translates to the Festival of the First Fruits. As Jews returned to Israel in the early 20th century, this aspect of the festival was revived, especially on the kibbutzim and moshavim—collective agricultural villages scattered throughout the country. To this day, Kibbutzim and other agricultural communities in Israel and around the world celebrate the holiday with a distinct harvest theme. On Shavuot we read the story of Ruth, one of the first and most well-known Jewish converts. She paved the way for many other lesser-known non-Jews over the years to discover and adopt our traditions. Anyway, Ruth was a Moabite woman who married this Israelite dude Mahlon during the period after the Jews entered the land of Israel but before Saul was named king. Unfortunately there was a famine that killed all the men in the family, leaving Ruth with her Israelite/Jewish mother-in-law Naomi and her Moabite sister-in-law Orpah. Naomi tells Ruth and Orpah they’re free to leave her and find new husbands. Orpah reluctantly leaves, but Ruth hits Naomi with one of those famous Biblical lines: “Don’t urge me to leave you or to turn back from you. Where you go I will go, and where you stay I will stay. Your people will be my people and your God my God.” So Ruth and Naomi move back to Israel and it’s right around the time of the harvest (one reason why it’s believed the book is read at this time). In Jewish law, you have to leave behind anything you drop in the fields during the harvest for poor gleaners. So Ruth is gleaning in the fields of this dude named Boaz. Long story short (not that long of a story), Boaz turns out to be a relative of Mahlon, which means he and Ruth are actually kinda supposed to get married. Also he’s really nice and they like each other so that works out nicely… and they get hitched. Best of all, their great-grandson is King David!! Woo!! We like him a lot, and can you believe his great grandma was a convert from a totally different tribe who immigrated to Israelite territory?? Almost like we shouldn’t be xenophobic and scared of people who appear to be different from us, idk, maybe I’m reading too much into it. Lastly but not leastly, we eat a lot of dairy foods on Shavuot! Which makes a lot of Ashkenazi (Eastern European) Jews get all: There are a lot of reasons why we do this, including but not limited to it being a reminder of the promise that the land of Israel will flow with "milk and honey" and that it’s the way we’ve always done it. And with that, I say Shabbat Shalom, Chag Sameach and have a wonderful three days!!

Ben Shalom y’all! Welcome to this week’s edition of Better Know a Jewish holiday! Today we’re celebrating Lag Ba’Omer, when Jews show off their fire and archery skills! So, what is the Lag Ba’Omer thing? What does it even mean? Why are we celebrating? What’s with the bonfires? Why did Ben get rid of that terrible-looking beard today? So, let’s start with what Lag Ba’Omer means. To do this, we’re going to work backwards. “Ba’Omer” means “of the Omer.” The Omer is a 49-day period between Passover and the next major holiday (coming up in a few weeks), Shavuot. Throughout the Omer we count every day to make sure we know which day we’re on: Historically, the Omer was the time it took for the Jews to travel from the Red Sea through the desert to Mount Sinai to receive the Torah. The Omer also marked the time of the barley and wheat harvest, and while the temple still stood, Jews would bring offerings of grain every day as part of the counting. “Lag” (pronounced “lahg”) is not even really a hebrew word, it’s simply a combination of the letters “ל” and “ג.” In a Jewish tradition known as “gammatria,” Hebrew letters each have a numeric value with the first letter of the aleph-bet (alphabet) assigned the number “1”, the second assigned “2” and so on. The letter “ל” has a value of 30 and the “ג” has a value of 3, so together they sound like “Lag” and have a value of 33. So Lag Ba’Omer is the 33rd day of the Omer. Overall, the Omer is considered a sad time, when Jews do not traditionally hold weddings or celebrations and many religious Jews do not cut their hair or shave their beards as a sign of mourning. Jewish mystics also see it as a time of spiritual cleansing. So now that we get that Lag Ba’Omer is the 33rd day of this counting between two holidays that is traditionally a sad period…. why is that a big deal? Why do we celebrate? There are two major traditions that surround Lag Ba’Omer, one is historical-political, the other more spiritual. The historical explanation for the holiday comes from the early 2nd century when Jews were living under Roman rule in the land of Israel after the destruction of the second temple. The Romans had put a number of harsh restrictions on the Jews, including preventing them from practicing their religion. One of the great Rabbis of this period was Rabbi Akiva. According to the Talmud, during the first 33 days of the Omer a terrible plague struck R. Akiva’s students because they did not act respectfully toward one another. According to the Rabbis, as many as 24,000 students died during this plague, which miraculously broke on Lag Ba’Omer. At the same time, R. Akiva was also supporting a rebellion against the Romans led by a man named Bar Kochba. R. Akiva and many of his students were killed when the revolt was crushed in 132 C.E. and some people believe the “plague” may have been hinting at this loss of life, while Lag Ba’Omer was a celebration of the efforts of the fighters. The spiritual celebration of Lag BaOmer centers around one of Rabbi Akiva’s students, Shimon Bar Yochai. According to tradition, Bar Yochai and his son lived in a cave with nothing but a pure spring and a carob tree for 12 years. While they were kickin’ it in the cave, Bar Yochai wrote the Zohar, the central text for Kabbalah (Jewish Mysticism). Bar Yochai is said to have died on Lag BaOmer, and every year hundreds of thousands of religious Jews spend the holiday at his grave outside Tzfat in northern Israel celebrating his life and his teachings. The bonfires lit by Jews at his grave and around the world are meant to symbolize the light Shimon Bar Yochai brought into the world with his teachings. Fire and light play a very important in Kabbalistic and Hassidic Jewish teachings. The Lubavitcher Rebbe often taught that “even a little light dispels a great deal of darkness.” Children also traditionally play with bows and arrows on Lag BaOmer. This tradition harkens to the rebellion that was underway in the time of Rabbi Akiva and are also symbolic of rainbows as the same word in used in Hebrew for both types of bows. Because it’s a day of celebration, the normal Omer restrictions are relaxed and people like me who are not good at growing out their facial hair can get a nice clean shave. So, with that I’m off to the barber, wishing all of you a fun and festive Lag BaOmer. Remember, treat each other with respect, and if you get stuck in a cave for 12 years, you better write a darn good book!

Welcome everyone to this week’s episode of Better Know a Jewish Holiday: Passover! The fightin’ feast of freedom! Passover (in hebrew: Pesach, PAY-sakh) is my personal favorite Jewish Holiday, primarily because it involves drinking, singing, philosophical discussion, and a great story. Passover, which starts tonight (Friday), celebrates the Exodus of the Jews from 400 years of slavery in Egypt. In part one of our two-part series, we will tell this story. In part two—coming later this week—we will delve into the traditions associated with the holiday. Admittedly, you could skip part one and watch The Ten Commandments, but it's 4.5 hours long. So, where do we begin? (Another Sound of Music gif was very tempting here). First let’s figure out why the Jews were in Egypt in the first place. The story told in Jewish households worldwide begins with the words “Arami oved avi,” “my father was a wandering Aramean.” So who is my father? What is an Aramean? And why was he wandering? Turns out the “father” here is Jacob. There was a famine in Canaan/Israel way back in the day and after Joseph took his Technicolored dreamcoat down to Egypt, he brought all of the Israelites down so they could have plenty of food. Fast forward a few years, and there came a Pharaoh who knew not Joseph. Pharoah’s priests and advisors—real anti-immigrant types—told him the Jews (who had stayed in Egypt once the famine ended) might rebel or join with his enemies if they attacked. Pharaoh decided there was only one way to deal with this issue: Build a wall!! Just kidding, instead he enslaved the Jews and force them to do hard labor. The Jews had been slaves for 400 years when another Pharaoh’s advisors told him that a prophecy foretold of a leader who would deliver the Jews to freedom. This Pharaoh decreed that all Jewish male babies would be put to death. Two midwives, Shifra and Puah (POO-ah, best name in the Bible) did not listen to the decree and helped Jews give birth without alerting anyone. When Pharaoh asked them where all the Jewish boys were, they were all like: One of those Jewish women, Yocheved (yo-KHEH-ved), gave birth to a baby boy and wanted to keep him from the Egyptians. To ensure his safety, she him in a basket and set him afloat on the Nile River, as one does. The baby really hit the jackpot when he floated right on down to the Pharaoh’s palace, where the ruler's daughter was playing in the river. She found the basket and declared that the baby would be raised as her own son and a prince of Egypt! The boy was called Moses and he grew up with all the trappings of royalty. But one day he saw an Egyptian beating an Israelite and he realized maybe this whole slavery thing is a really bad idea. Because he was raised in a violent patriarchal society that emphasized confrontation over dialogue, Moses did not have the tools to handle his newfound feelings of empathy. So he killed the Egyptian and buried him in the sand. When Pharaoh heard what had happened he wanted to kill Moses, but the young Israelite was too quick and had already fled to Midian. While there he got married, herded sheep, and was living a good life on the lam(b) until one day he saw a burning bush! G-d spoke to Moses from the and told him to go back to Egypt, confront Pharaoh and free the Jews! Moses, who had a speech impediment and did not yet realize he was handi-capable was all like: Despite his initial reluctance, Moses eventually agreed to do as G-d/the Bush told him to once he showed him a few minor miracles. So Moses went back to Egypt, set up a meeting with the Pharaoh and laid out his demands: Pharaoh was unimpressed, and didn’t even budge when Moses showed off G-d’s power by transforming his staff into a serpent. Pharaoh refused to let the Jews leave Egypt, so G-d (via Moses) unleashed ten plagues on the Egyptians. The first nine were—in a very particular order: The Nile turning to Blood, Frogs, Lice, Wild Animals, Cattle Disease, Boils, Hail (and fire), Locusts and Darkness. The plagues really wrecked havoc on Egyptian society. There’s actually some really interesting and troubling philosophical issues here, because 1) this is serious collective punishment for Pharaoh’s intransigence and 2) after many of the plagues the Torah tells us that G-d “hardened Pharaoh’s heart,” making him unwilling to let the Israelites go free. One of the great things about Passover is that we discuss the story in depth and we try to wrestle with some of these quandaries. It’s a holiday that’s more about the questions than the answers. The last and most devastating plague was the Death of the Firstborn. In the middle of the night, G-d struck down the firstborn son of every Egyptian household. Jewish homes were passed over (GET IT?!?!?!) because they had lamb’s blood on their doorposts and lintels. Once this the final plague was complete, Pharaoh at last had enough and ordered the Jews to leave. They left really fast, not even giving their bread enough time to rise. It’s a good thing too, because Pharaoh was all like: And he forgot the cardinal rule: He chased after the Jews who were just reaching the Red Sea. When it seemed as though all was lost, G-d split the sea and the Jews were able to walk through on dry land. Pharaoh and his chariots were not so lucky. So there you have it, the story of Passover. The Jews wandered off into the desert where they'd be for 40 years. They had many fun adventures and hijinks including getting the 10 Commandments from G-d, the Golden Calf and that one time they ate so much quail everyone got super sick and they inspired a super hero. Chag Sameach!

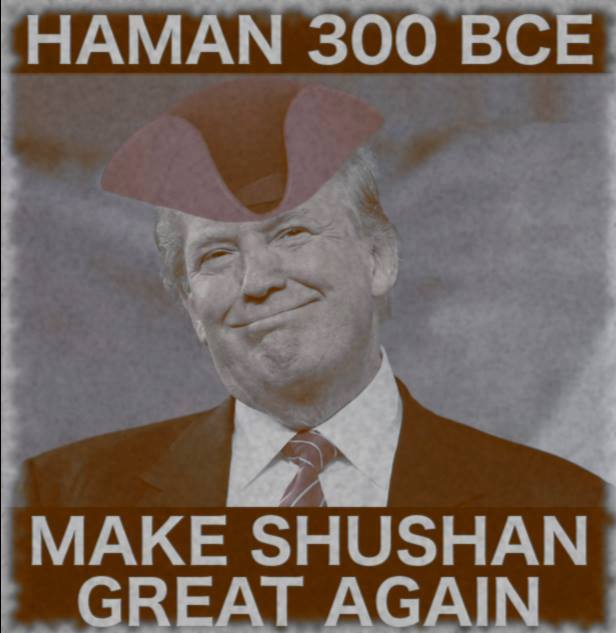

Shalom y’all! Welcome to the latest Better Know a Jewish Holiday! Today’s episode is Purim! The fightin' festival of festivities! Purim is essentially the Jewish Halloween—if Halloween had mandatory drinking, a story with some positive morals, and female empowerment! Purim, like Hanukkah, falls into the classic “They tried to kill us, they failed let’s eat,” Jewish Holiday trope. It all begins with a huge party thrown by Achashverosh (ah-CHASH-veh-ROSH), the king of Persia: We’re talking a weeks of Party Rockin’ in a row!! Anyway, at some point Achashverosh decides he wants to show off his wife Vashti and demands that she come dance for him and all of his viziers. Instead, Vashti channeled her [insert your favorite feminist icon] and was all like: After Vashti refuses to dance, Achashverosh banishes her (naturally) and then has to figure out what to do about the whole not having a wife situation. So he has a “beauty contest” for all of the lands he owns, a territory stretching from Ethiopia to China. Participation rates were high, the winner got to be the King’s wife. Haddassah was a Jewish orphan living in the capital city with her uncle, Mordichai (More-de-khai). He insisted she change her name to Esther and throw her proverbial hat (read: hymen) into the ring for the King’s heart and she was all like: Of course after much primping, Esther is the most pleasing to the King and becomes the Queen! Unfortunately, right about this time Haman Haman (pronounced HAY-man or hah-MAHN depending on whether you’re feeling Israeli or American) was promoted to grand vizier and got a little power hungry Haman was a megalomaniac xenophobe who thought that everyone needed to bow down to him and respect his authority. He was very very unpleased when Mordechai, citing his First Amendment right to freedom of religion, refused to bow down and was all like Haman decided the rational retaliation for this slight was to slaughter all of the Jews in the kingdom. So he cast lots called purim—hence the name of the holiday—to determine when to annihilate the Jews and landed on the 14 of Adar (the day of the holiday). When the Jews heard about this plan, they were understandably very upset: Mordechai went to Esther and was all like: This is your moment! You have to save us all! Esther said she would go to see the king, but requested that everyone fast with her for three days beforehand. We observe this fast for one day these days, which is why I won’t be able to eat any food on my last day at work Wednesday. So sorry if I get like this sometime around 5 p.m. tomorrow… After fasting, Esther went before Achashverosh and said she had a favor to ask. Achashverosh said she could ask for anything up to half his kingdom! One might think she could have just gone for that and asked all the Jews to move in to her half of the kingdom, but then the story would not have been as good. Instead, she invited the king and Haman to a lavish feast. At the feast Achashverosh again made the half kingdom offer, instead, she invited them to a second feast. Now at this feast she finally reveals that she is Jewish and that Haman’s decree would mean she would be killed to!! Haman, in a strange move, throws himself at Esther begging for mercy. Problem is it kinda looked like he was attacking her. Bad move Haman, never attack the queen in front of the king. The king has Haman hung on the same gallows he built for Mordichai Mordichai is appointed the new grand vizier and it seems that all is well with the world. However, weirdly, the King says he cannot reverse his decree, so instead of saying that Jews can’t be killed, he makes it legal for the Jews to fight back. You know what that means: Anyway, the Jews fight back, kill lots of Persians who thought they were going to kill lots of Jews and everyone’s happy! To celebrate Purim we listen to a reading of the story, give gifts to friends, give charity, eat a feast, and get rulllll drunk: We also traditionally eat Hamentashen, a yiddish word meaning Haman’s pockets, are a triangle cookie with yummy fillings we eat. Depending on who you ask they represent Haman’s ears, his hat or any number of other things. No matter who you ask, they are delicious: Well, that’s all folks. As always, feel free to share with friends and family and if you have any questions please reach out or leave them in the comments. Happy Purim!! If I have time between Hamentashen baking on Thursday I'll be back with some fun additional stories and points of intrigue.

|

About the JewThe Jew is an Uber driving, Bar Mitzvah DJing, yoga teaching ex-journalist from Ann Arbor, Michigan who attends rabbi School in NYC. Archives

October 2018

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed